LESSON 1

what is biodiversity documentation and why is it important?

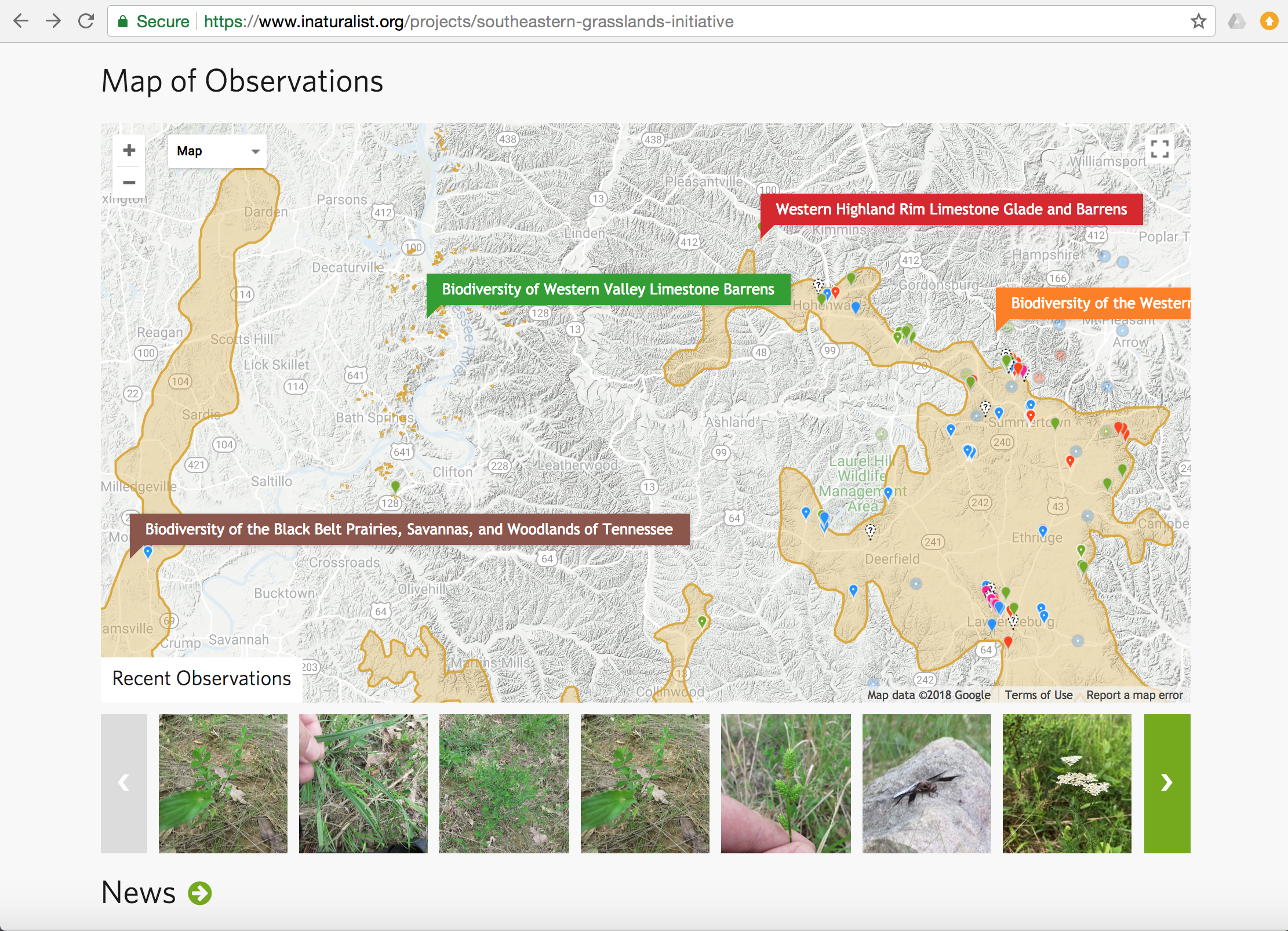

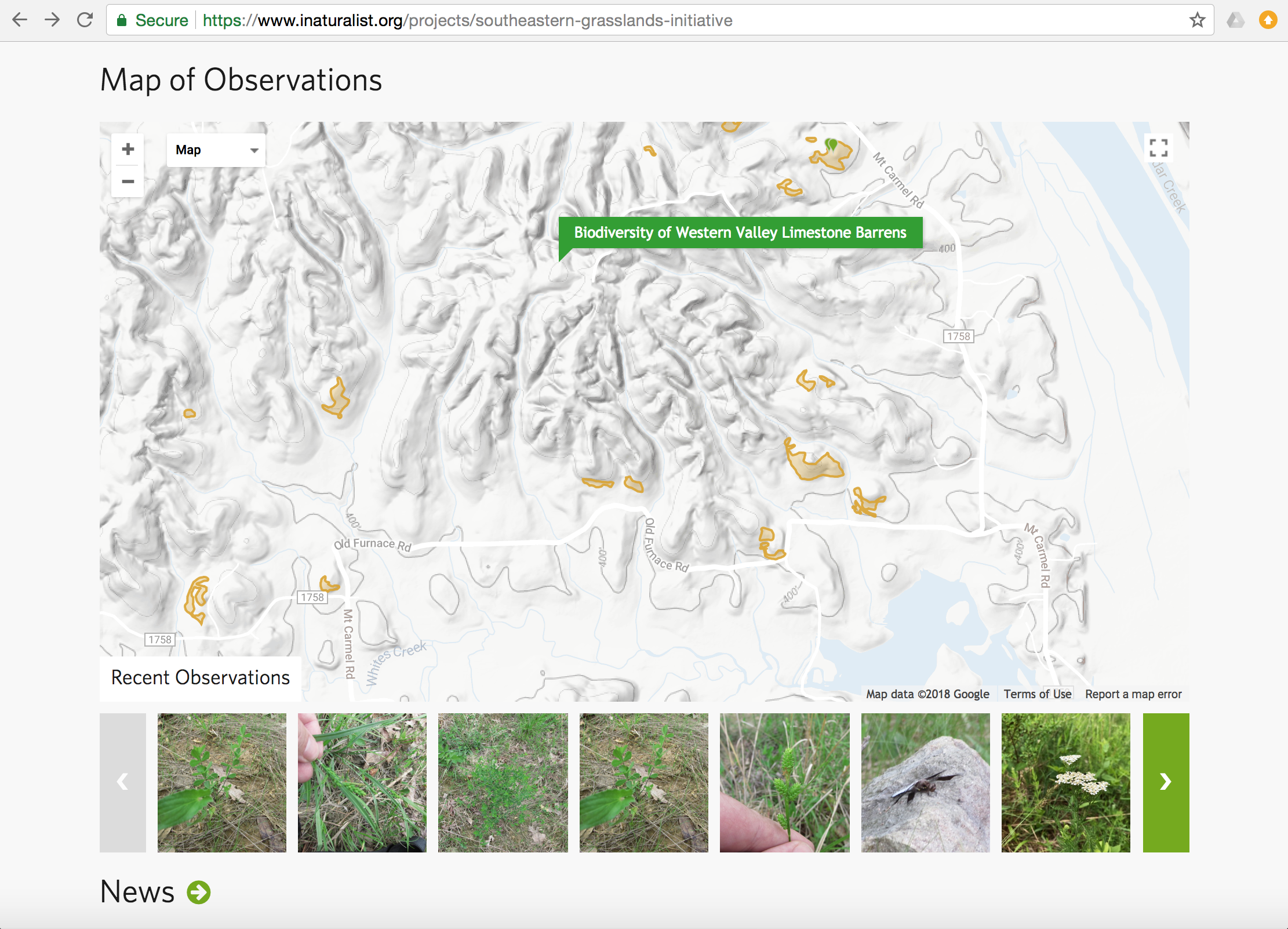

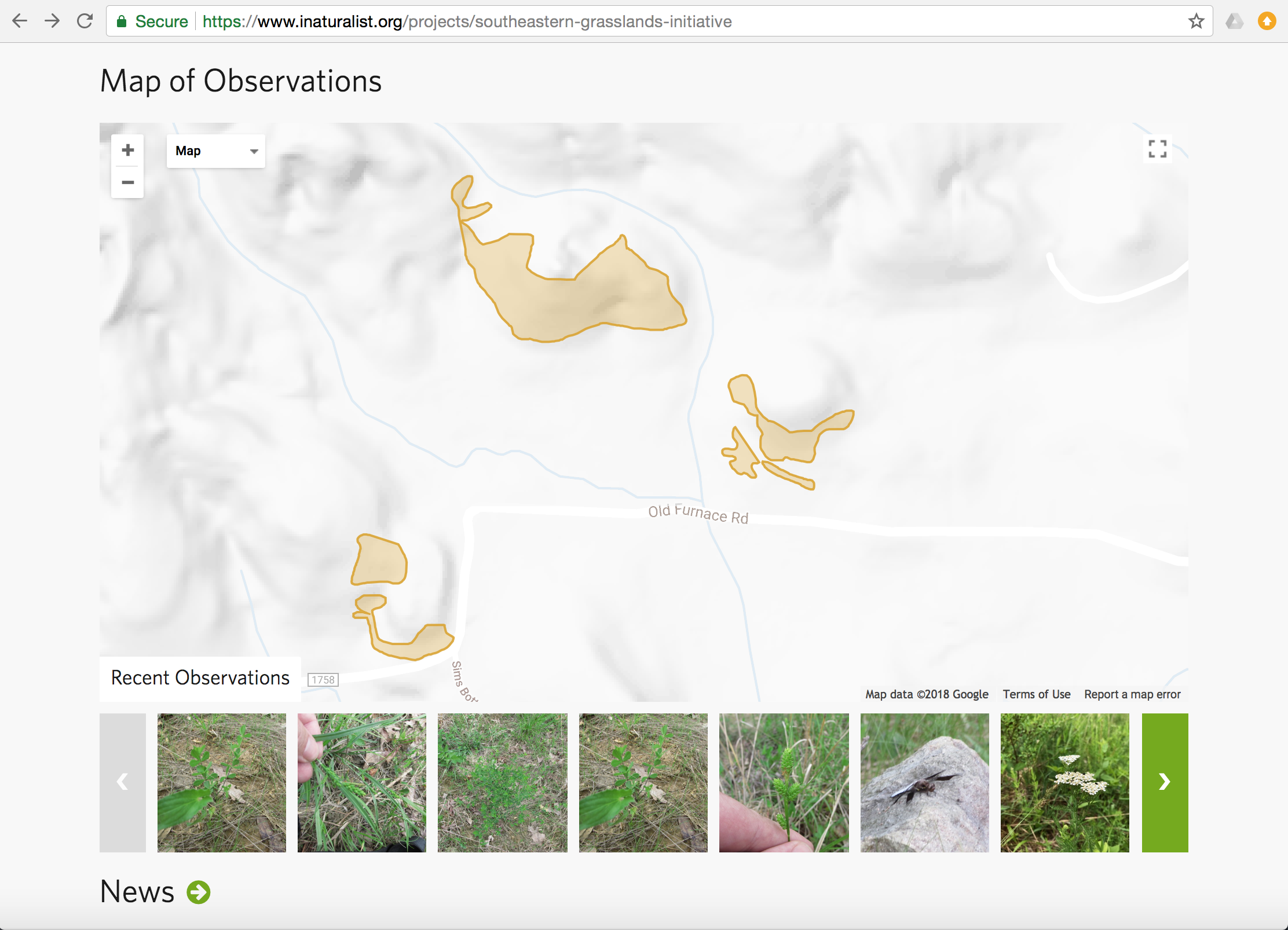

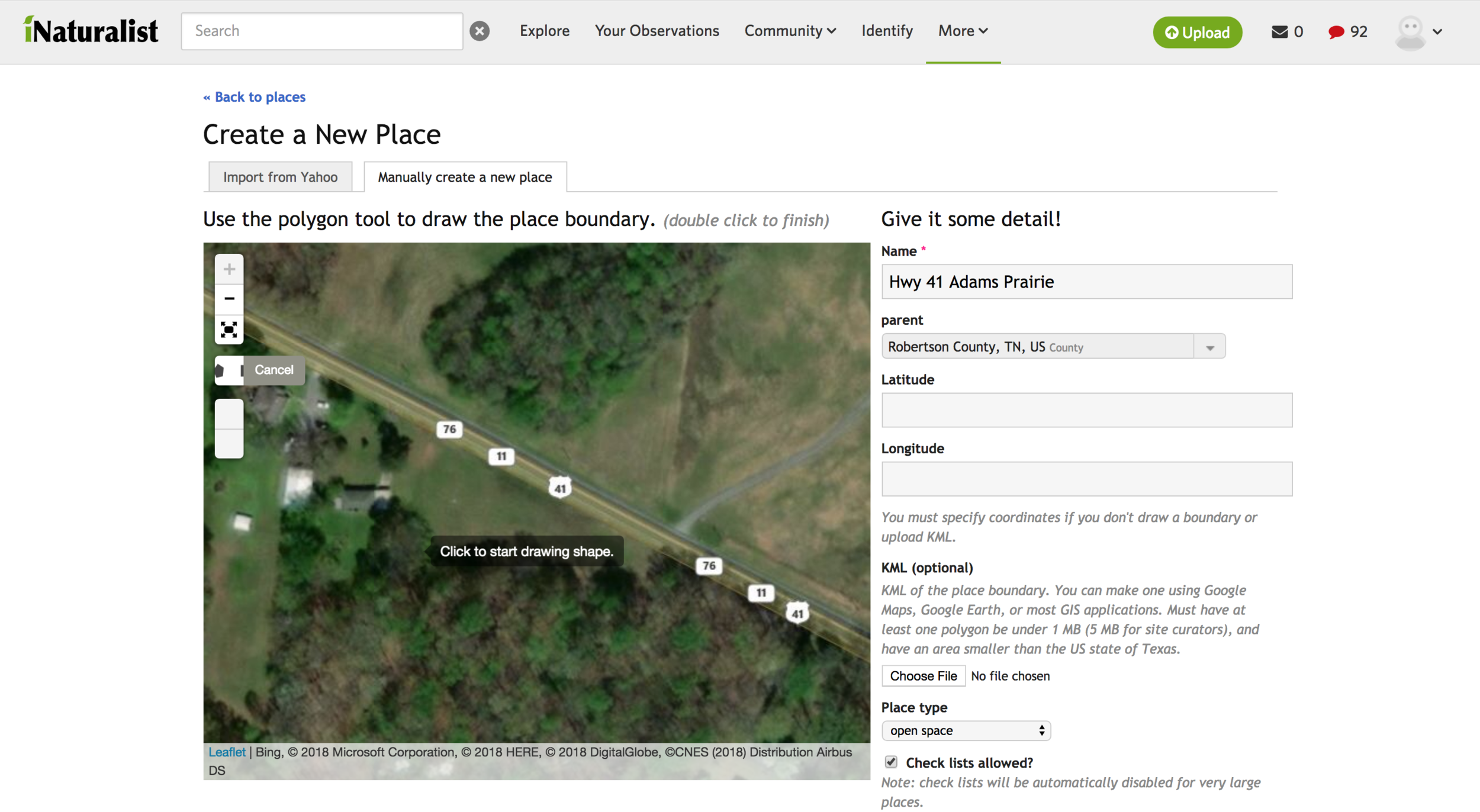

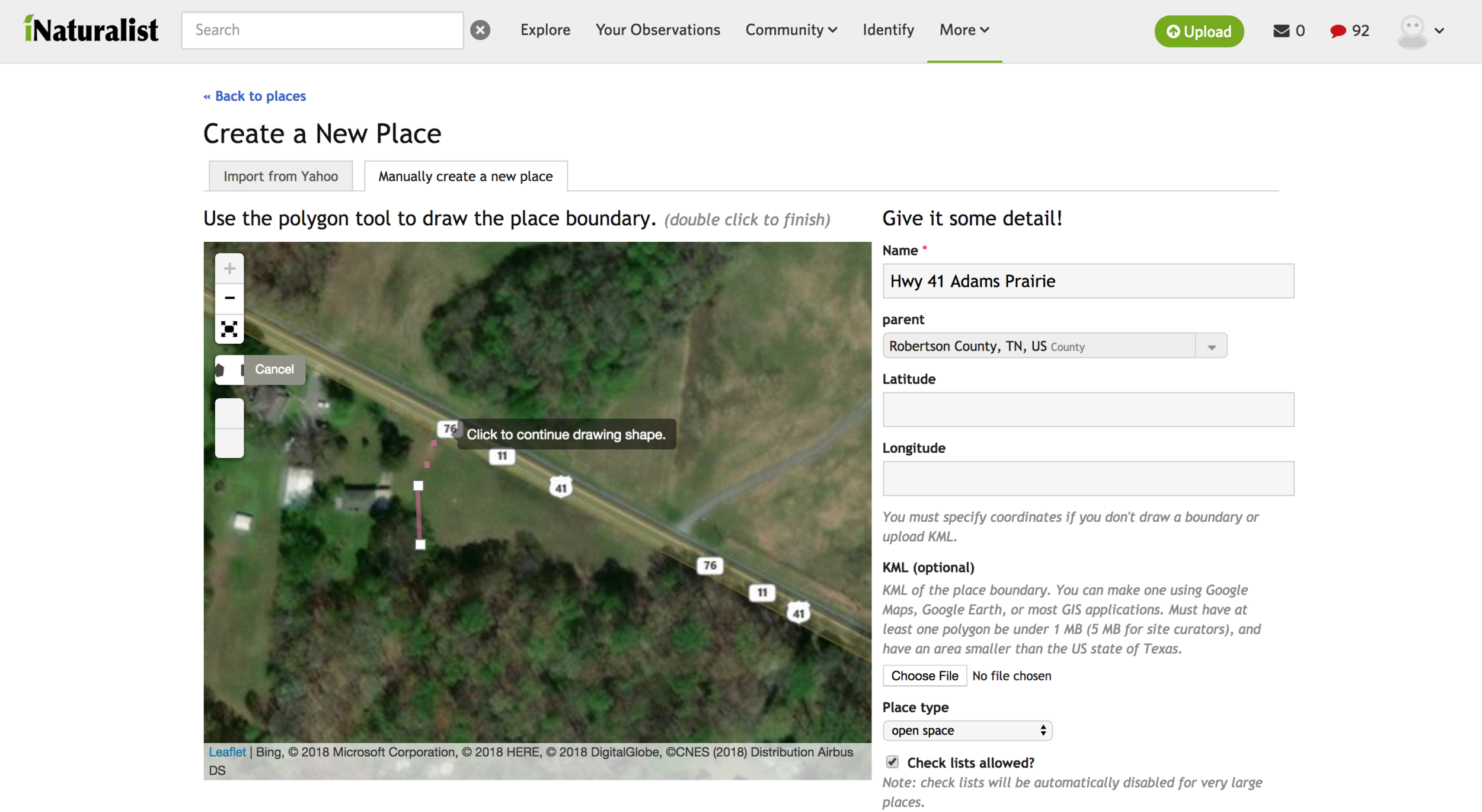

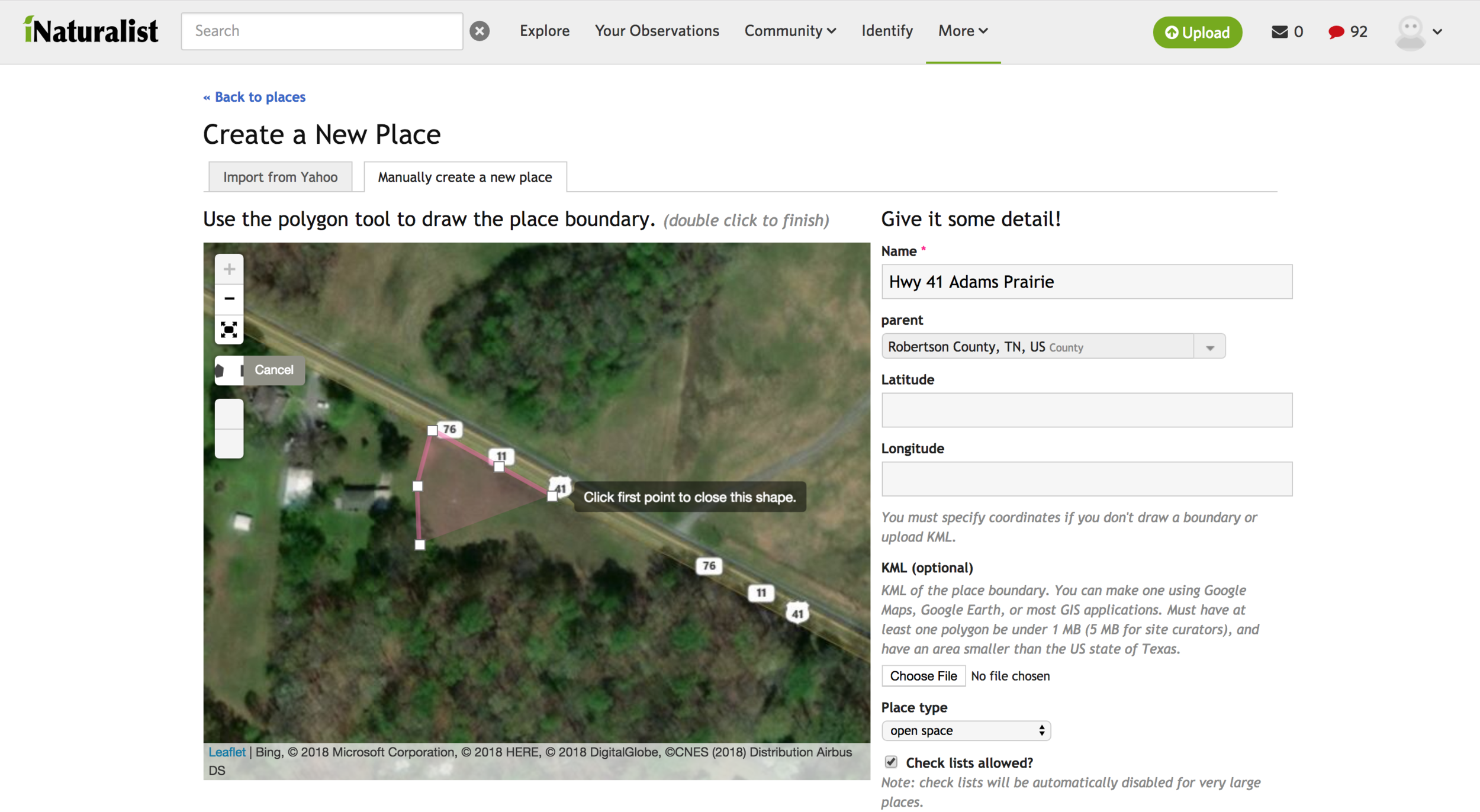

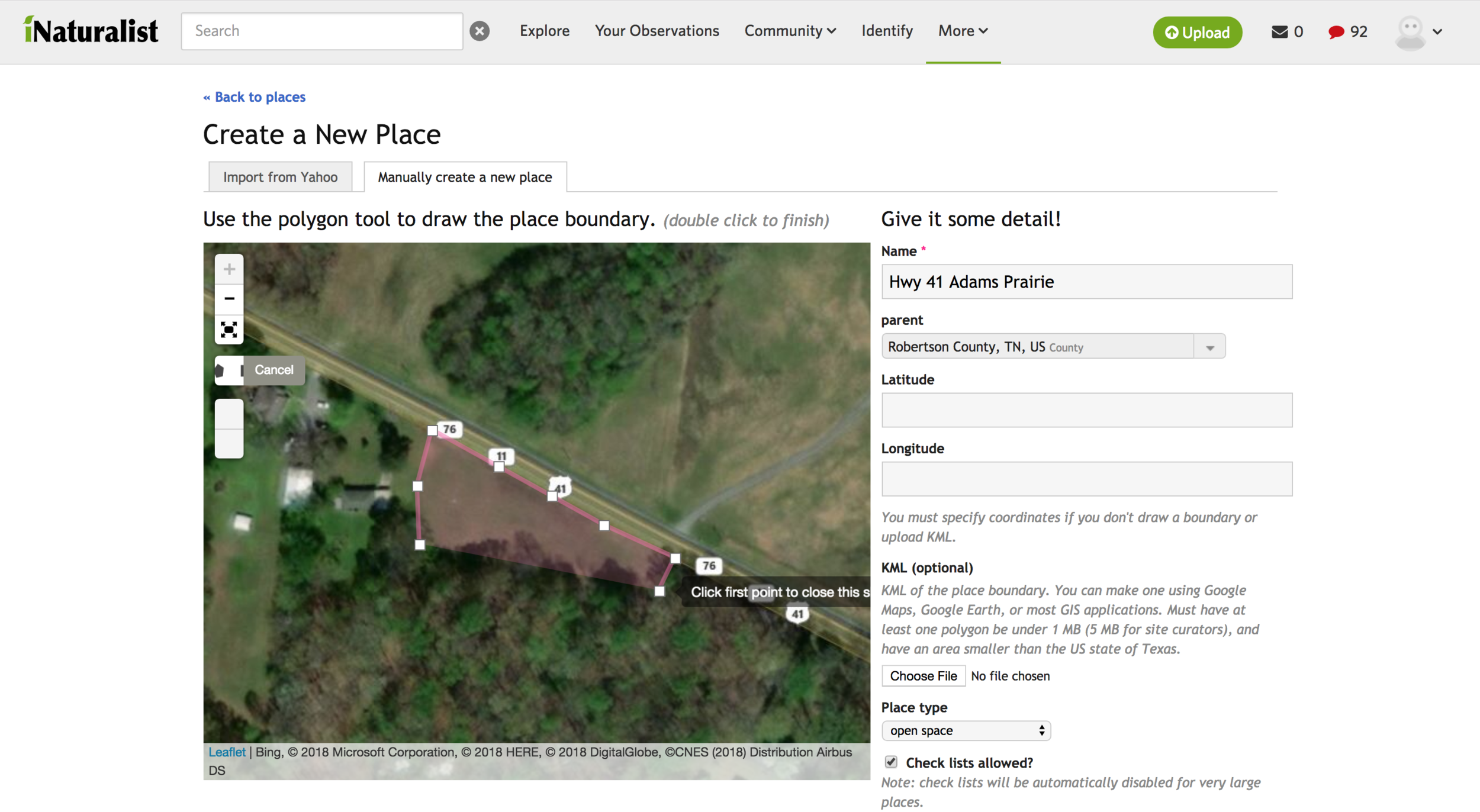

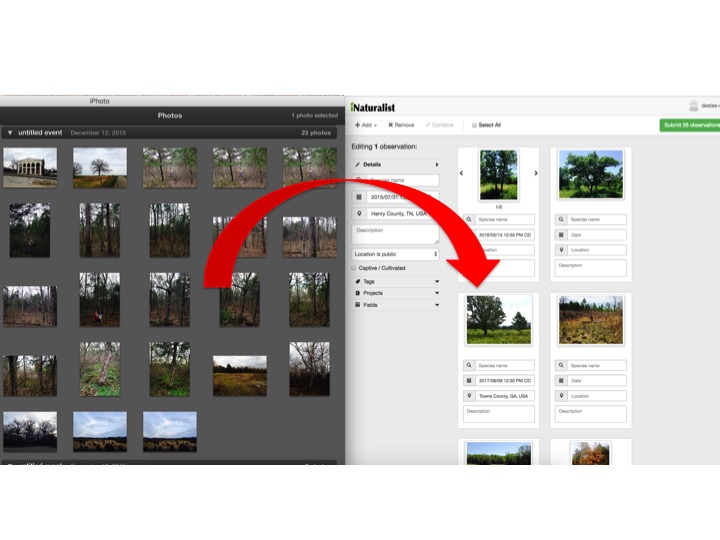

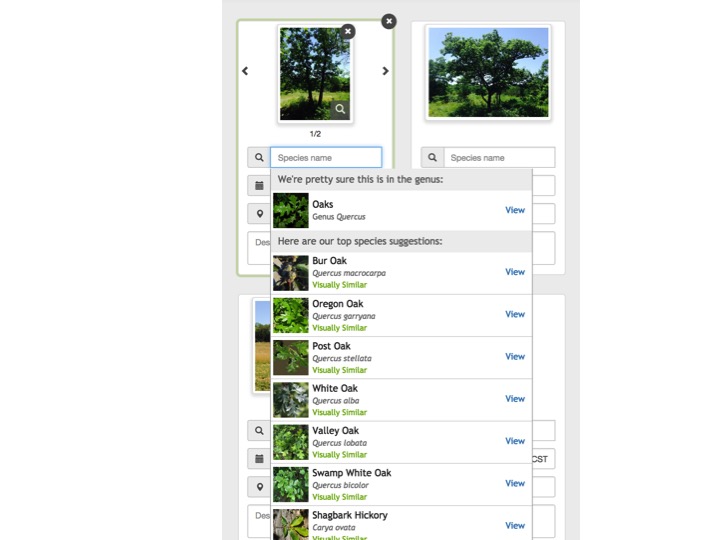

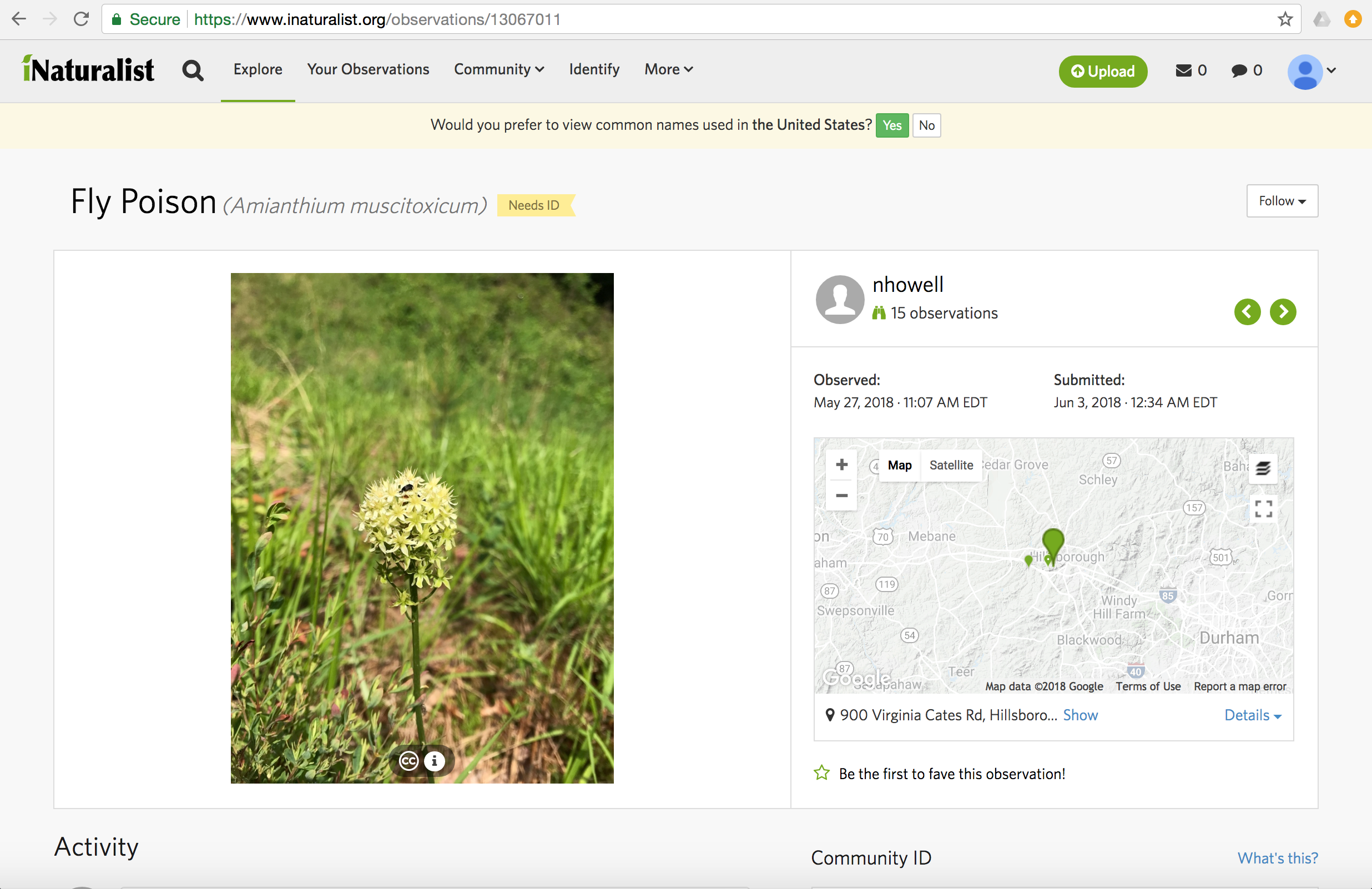

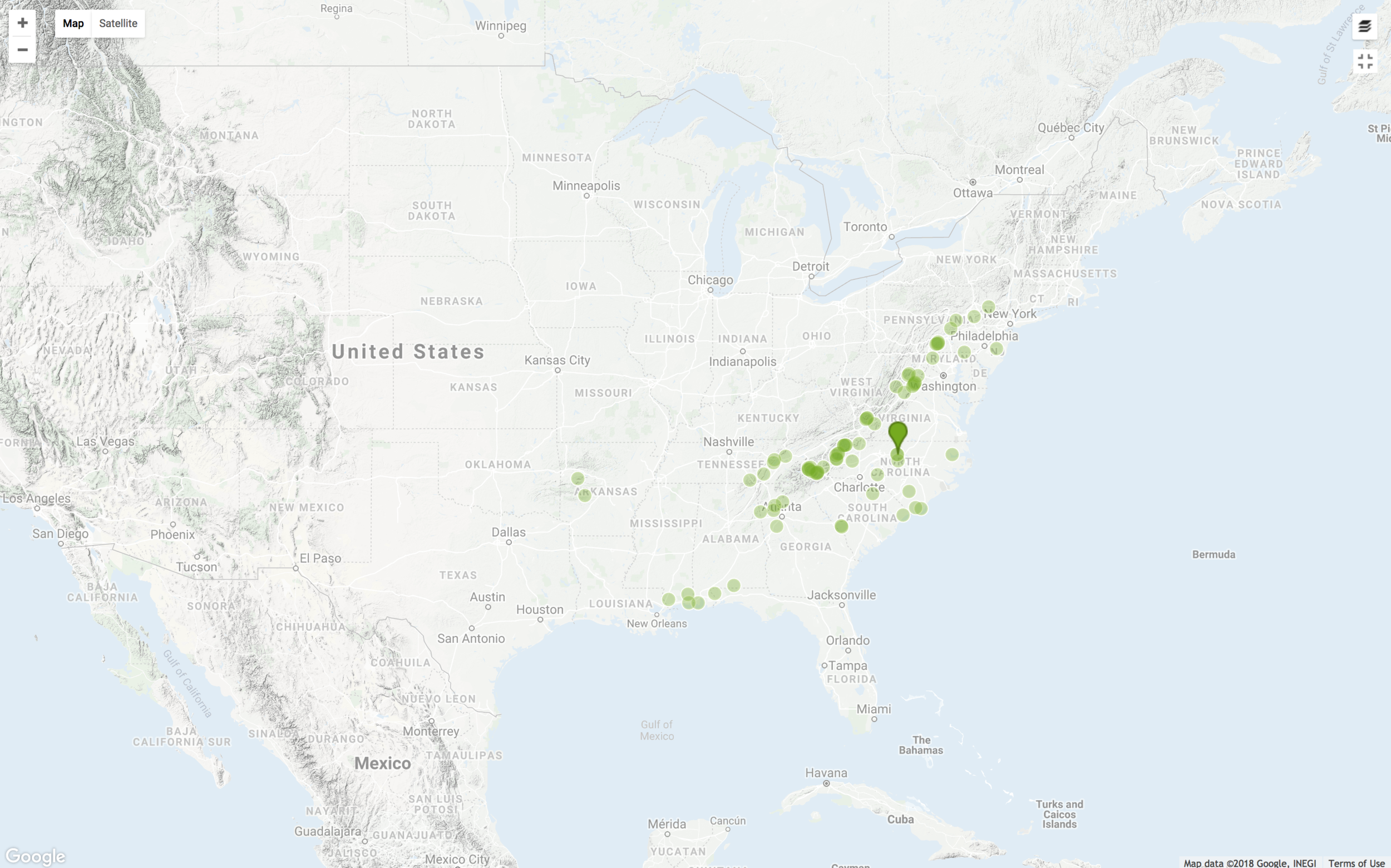

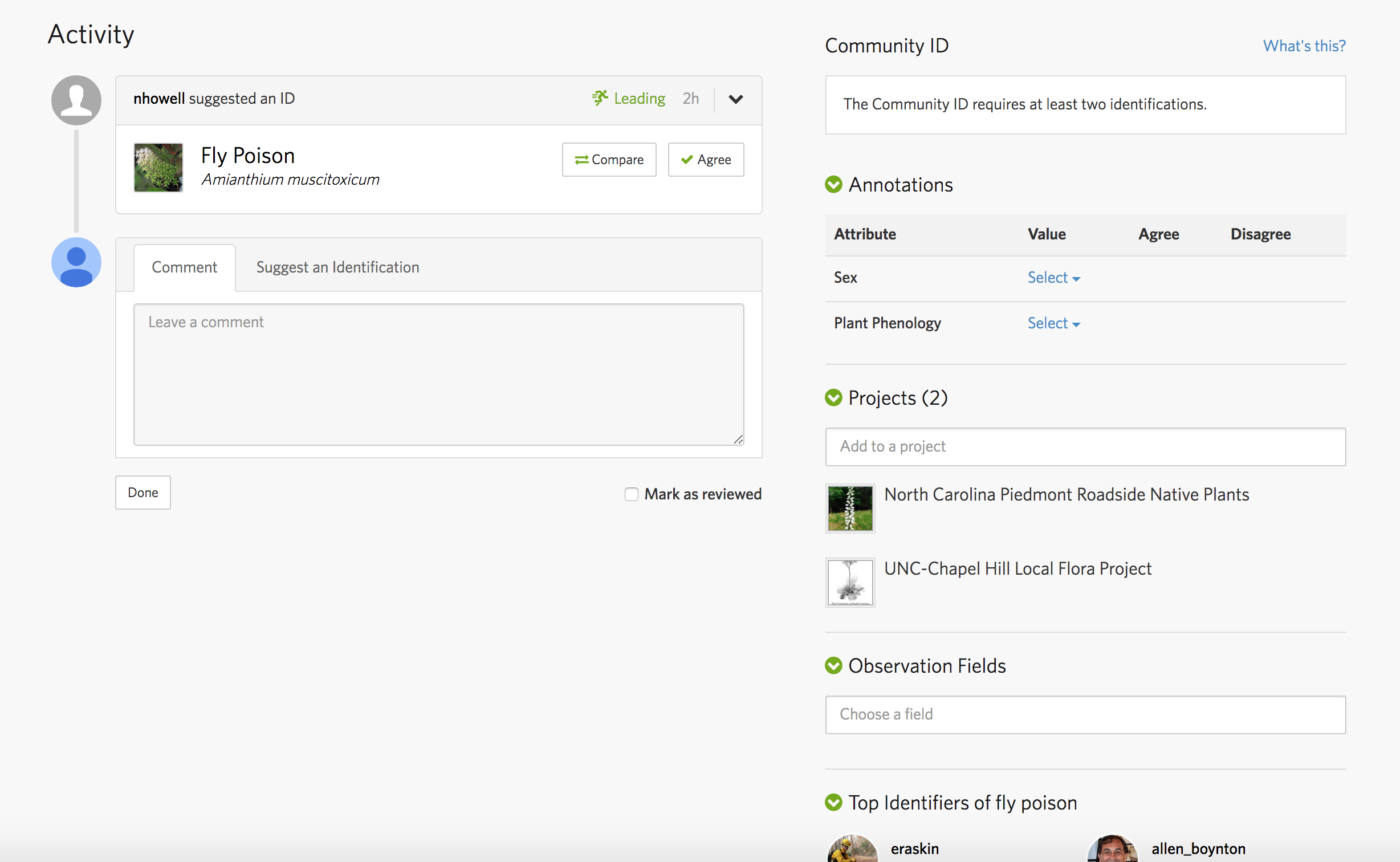

Biodiversity documentation is the process of identifying/recording species of plants, animals, fungi, etc. in a given area such as a prairie remnant. Methods to document may include photography, sound recordings (for birds and frogs), and collection of voucher specimens such as pressed plant specimens or butterflies (note permits are needed in some areas for specimen collection such as on public lands). Until recently, much of the work being done to document biodiversity has been done by professional conservationists who have received training in university classes, workshops, etc., mostly using published field guides or identification manuals to identify species. Now, thanks to recent technological advancements, it is now possible for a wide range of people to play leading roles in biodiversity documentation thanks to iNaturalist. This program is easy to use, whether you are 13 or 90 and whether you have a PhD in rocket science or are an eighth grade student who loves butterflies. It gives the average person the power to identify potentially thousands of species.

step 1 -- how do I get started?

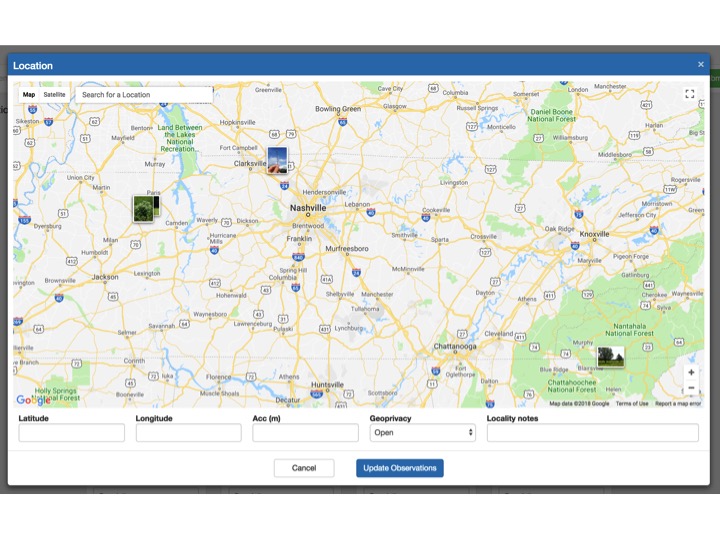

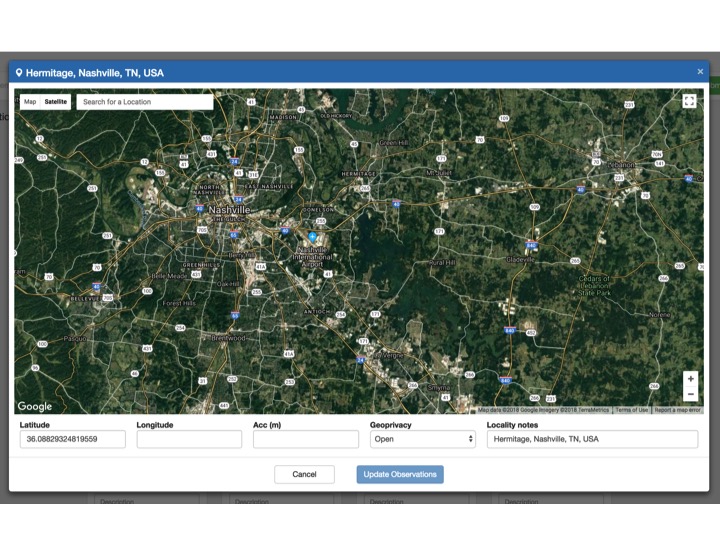

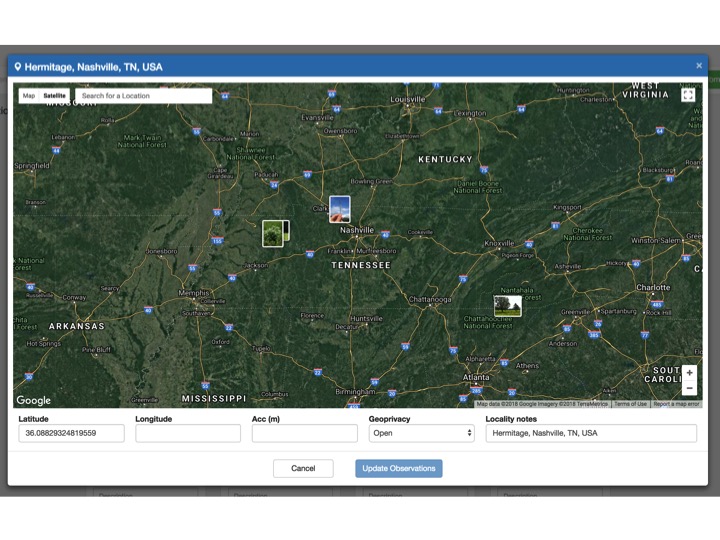

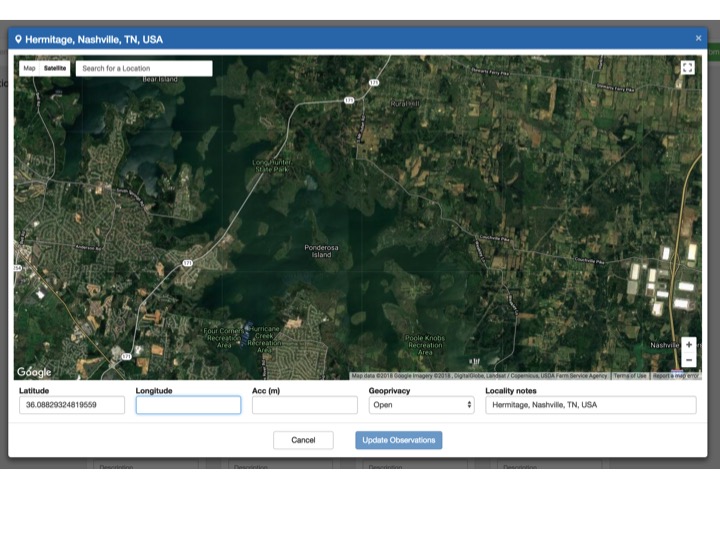

Download iNaturalist on your smartphone or tablet to Explore, Learn, Record.