Reversing Declines in Grasslands Biodiversity

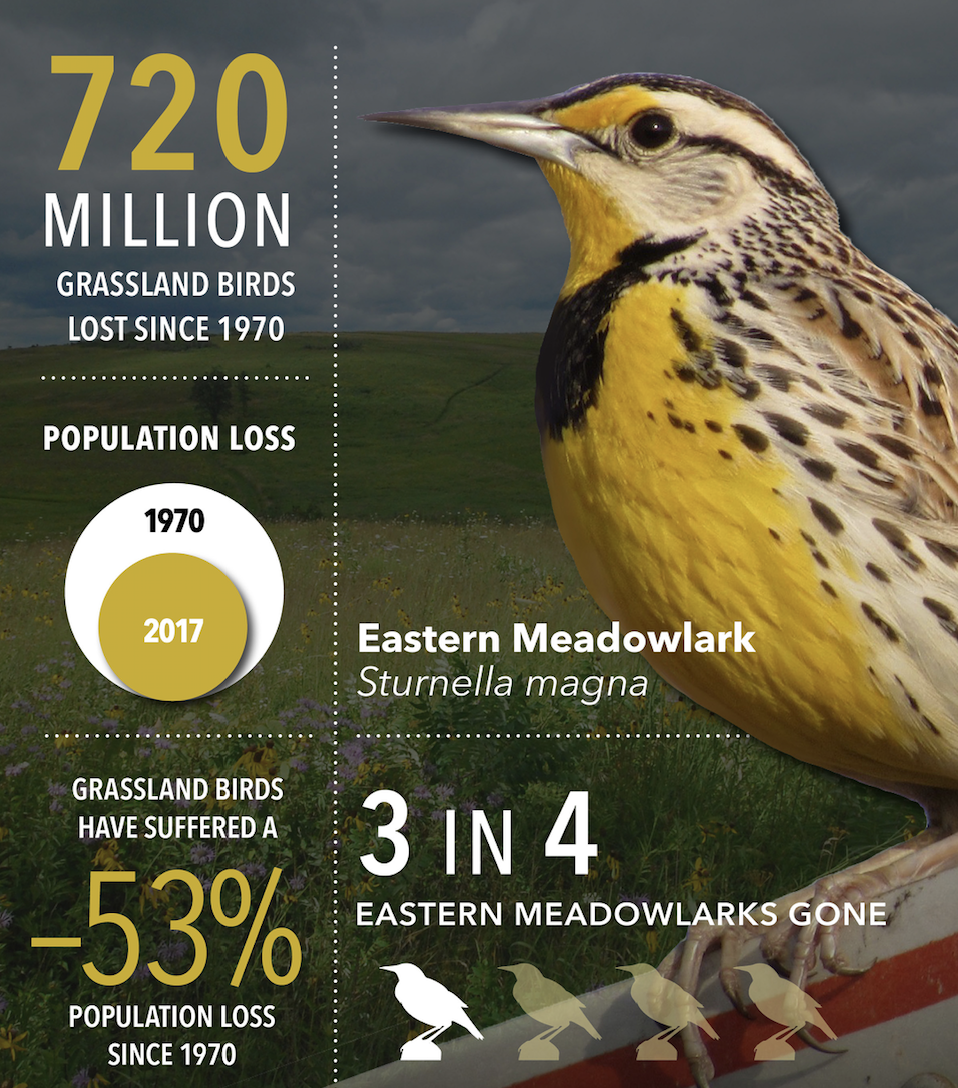

The Southeastern U.S., which is roughly 85% private land, has experienced widespread losses (90 to 99%) of its native grasslands. In fall 2019, research published in the journal Science, found that since 1970, bird populations in the United States and Canada have declined by 29 percent, or almost 3 billion birds, while grassland birds have suffered losses in excess of 50%!

Graphic courtesy of Cornell Lab of Ornithology

For this reason, a big focus for SGI is addressing the lack of adequate habitat for wildlife and at-risk species experiencing widespread population declines by working to restore native grasslands on private lands across the Southeast. As part of a 10-partner team led by the American Bird Conservancy/Central Hardwood Joint Venture, SGI is helping to implement a project under the USDA NRCS’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP), with a focus on private land conservation in areas that can augment grassland habitats in federal and state protected areas.

Our RCPP partners are

Nonprofits

State agencies

Federal agencies

Businesses

Bridgestone Americas Tire Operations, LLC

SGI’s team of three Farm Bill staff are employed by partner Quail Forever, but are supervised and based out of SGI’s headquarters on the Austin Peay State University campus. Their critical role is to help focus Farm Bill funds (under the EQIP, CSP, and WRE programs) from NRCS by assisting landowners to improve their land in ways that will help recover (a) populations of three key grassland bird species deemed in need of conservation attention and (b) the native biodiversity associated with the historic grassland landscapes of the Interior Low Plateaus ecoregion of Tennessee and Kentucky.

Habitat improvements for Eastern Meadowlark, Northern Bobwhite, and Henslow’s Sparrow—the project’s focal bird species of concern—can largely be accomplished by opening up suppressed native grasslands with removal of woody cover and prescribed fire, replacement of cropland or fescue pastures with mixes of native grasses and forbs, increasing forb-to-grass ratios, changing grazing intensities, and altering mowing/haying regimes. These efforts can employ lower-diversity seed mixes of 5-20 species, but restoring both vegetation structure and significantly increasing native biodiversity will generally require seed mixes of 20-50+ species.

Focal species for conservation

This species is a common bird in steep decline. According to the State of the Birds 2011 report, more than 95 percent of the Eastern Meadowlark’s distribution is on private lands, meaning farmland conservation practices are vital to the survival of this species. Losses are due to their disappearing grassland habitat. Prairie is scarce in the eastern United States, and the kinds of farms that once hosted meadowlarks—small, family farms with pastureland and grassy fields—are being replaced by larger, row-cropping agricultural operations or by development. Early mowing, overgrazing by livestock, and the use of pesticides can also harm meadowlarks nesting on private lands. There are many locations where glades and woodlands have simply been degraded over time and can be restored with thinning to open the canopy and fire to stimulate the groundcover. However, most of our prairies and barrens, with their deeper soils, have been completely converted to non-native grasses and cropland, and those need to be reseeded or replanted with native vegetation as an initial step in bringing them back. The Southeastern Grasslands Institute is emerging as an important ally in those efforts by developing locally-adapted native seed sources that can be used to recreate native communities with a grassland component.

Henslow's Sparrow does not have federally protected status in the United States, but is listed as Endangered in seven states, as well as Canada. Henslow's Sparrow has been identified as the highest priority for grassland bird conservation in eastern and midwestern North America by Partners in Flight (PIF), a cooperative effort of many organizations dedicated to bird conservation. PIF is promoting establishment of large grassland conservation areas for this and other species.

Widespread, sharp declines between 1966 to 2014, up to 4% per year, resulting in a cumulative decline of 85%, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The bobwhite’s decline probably results from habitat degradation and loss owing to urbanization, fire suppression, and changes to agriculture and forestry. Agricultural fields have become less suitable for bobwhites with higher levels of pesticides and herbicides yielding less insect and plant food, and fewer hedgerows to provide cover. In economic terms, the Northern Bobwhite was one of the most important game birds in North America. Population declines from habitat loss now mean that in many places there are no longer enough to hunt.